Image: WordsmithChristine.com

I recently spent some time in Freddie Gray's West Baltimore neighborhood asking local women for their thoughts on police reform.

I was curious because, as the Freddie Gray trials drag on, I can't help but feel that city and state officials are failing to ask everyday people what needs to change. And I mean ask them directly, in ways that acknowledge that they have real lives with real responsibilities and may or may not have reliable transportation or Internet at home.

Last May, Maryland set up a police reform task force to make legislative recommendations to the General Assembly. Yet most of the public hearings took place during business hours in Annapolis, which is a 45-minute drive from Baltimore. As a result, the hearings were poorly attended, particularly by the people who had the most at stake — residents of low-income, historically Black, urban neighborhoods.

As a woman, I was especially interested in hearing what women in and near Sandtown-Winchester had to say. So I stopped them on the street and approached them at bus stops — and when they were willing to talk to me, I listened.

Many of the women I encountered were young, single mothers. Some of them expressed concerns about raising their children in the neighborhood. They didn't want their children to grow up and get harassed by the police. They didn't want them to get hurt by gangs or get involved in the drug trade. These women aren't being paranoid. They have good reason to worry.

Sandtown-Winchester is the “other” America — 72 square blocks of the kind of community you would never see on a postcard. The neighborhood, once known as Baltimore's Harlem due to its bustling culture and commerce, has watched its population decline for decades. In 1990, 11,000 people lived here.

Currently, Sandtown, as the locals call it, is home to 8,500. And it shows. With one out of every three buildings vacant or abandoned, boarded-up doors and windows are a common sight. There's very little greenery, and there are no grocery stores.

The LA Times called the neighborhood “'The Wire' in real life.” Normally I bristle at comparisons between the HBO show and the real Baltimore, but Sandtown is a reminder that the distance between fact and fiction is not always so great. In this neighborhood, crime and desperation are the reality. That's not a judgment of the people who live there: It's an indication that America has to do better — for all of its people.

Sandtown mothers are brave — especially since more than a third of them head single-parent households.

Here are the top nine challenges that many of the neighborhood's mothers face every day:

1. Healthcare

The average life expectancy of Sandtown residents is 65. Heart disease, diabetes, and cancer all are relatively common.

Then there's the issue of barriers to care. Perhaps the best examination of those barriers you'll find is the series “In Poor Health” by Kaiser Health News and Capitol News Service. Check out this chart showing how Freddie Gray's neighbors are hospitalized with life-threatening conditions at rates far above the city and state averages.

2. Housing

Affordable housing is a problem, as are negligent landlords and lead poisoning due to old lead paint remaining in old houses.

More than 3% of local children under age 6 have potentially dangerous levels of lead in their blood (just as Freddie Gray did). FiveThirtyEight.com calls the city's epidemic “a toxic legacy."

3. Under-education

Just over a quarter of the neighborhood's adults above age 25 have a high school diploma. If you include GEDs, the number jumps up to 66%. However, only 6% of Sandtown residents have a college degree.

Limited education means limited job opportunities, as well as limited power and awareness when it comes to advocating for their families and their community.

4. Unemployment

Less than half of the neighborhood's residents aged 16 to 64 have jobs. That's double the unemployment rate for the rest of Baltimore.

It's no surprise, then, that poverty prevails. The median household income in Sandtown is about $24,000 for a family of four.

That makes the annual cost of childcare ($8,000+) seem pretty unrealistic.

5. Public Transportation (Or Lack Thereof)

While getting around Sandtown may not be difficult, getting out of it is much trickier.

In an op-ed for The Baltimore Sun, Odette Ramos wrote that “efficient public transportation” is even more crucial than neighborhood job training programs. “Job training programs in Sandtown,” she continued, “do little to help residents if there's no way for them to reach workplaces in the suburbs.”

6. Drugs

Baltimore is the nation's heroin capital. And West Baltimore neighborhoods like Sandtown, which is home to the Tuerk House treatment program, are particularly afflicted.

“I think the social degradation of the community directly impacts addiction,” writes Stanton Peele in Pro Talk, a Rehabs.com community. “I also think there is no answer to addiction that doesn't address such problems. And if they aren't addressed, there's no reason to expect drug addition to decline in Baltimore any time soon, no matter how many people are enrolled in rehab.” I couldn't have said it better myself.

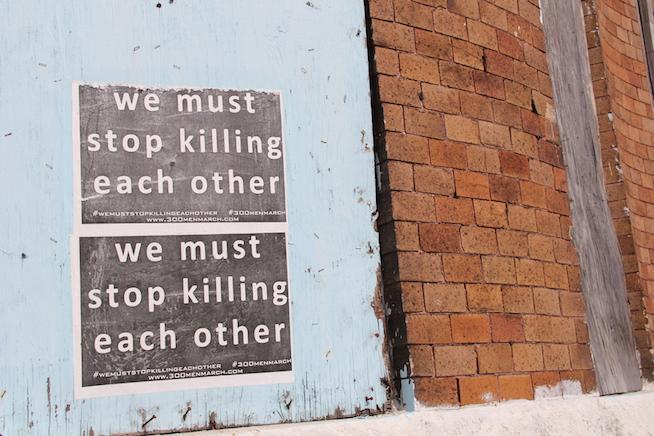

7. Violence

The real estate website Point2Homes.com puts Sandtown's rate of personal crime risk, murder risk, rape risk, assault risk, and robbery risk all well above the national average. After Baltimore's Uprising last year, murder levels in West Baltimore reached the highest they had been in 40 years.

8. Police

Policemen who perform the duties of their job as intended are heroes. The ones who don't — whether in Baltimore or elsewhere — harm the places they're supposed to protect. The women I spoke to while reporting said that many local police are rude at best and brutal at worst.

I can objectively say I had never seen so many police cars and officers in a single neighborhood before. Rather than being protected, the people of this neighborhood are being policed.

9. Incarceration

In a place where drug-related offenses are commonly prosecuted, Sandtown has the state's highest incarceration rate. (Freddie Gray himself was arrested for drug-related offenses more than a dozen times.)

According to the Justice Policy Institute, instead of throwing tax dollars at prisons, those funds could be invested “in an array of programs and resources already available to help address community challenges.” Check out the cost per person for adult drug treatment, employment training, and more here.